Ania Ready

Ania Ready is a visual artist working with photography. She is of Polish origin and based in the UK. Her work centres around notions of belonging and alienation, memory and amnesia, mental fragility and poetics of existence. Her work has been presented at the Modern Art Oxford, Pitt Rivers Museum, Humanit’Art Gallery, Auckland Photo Festival in New Zealand, and elsewhere.

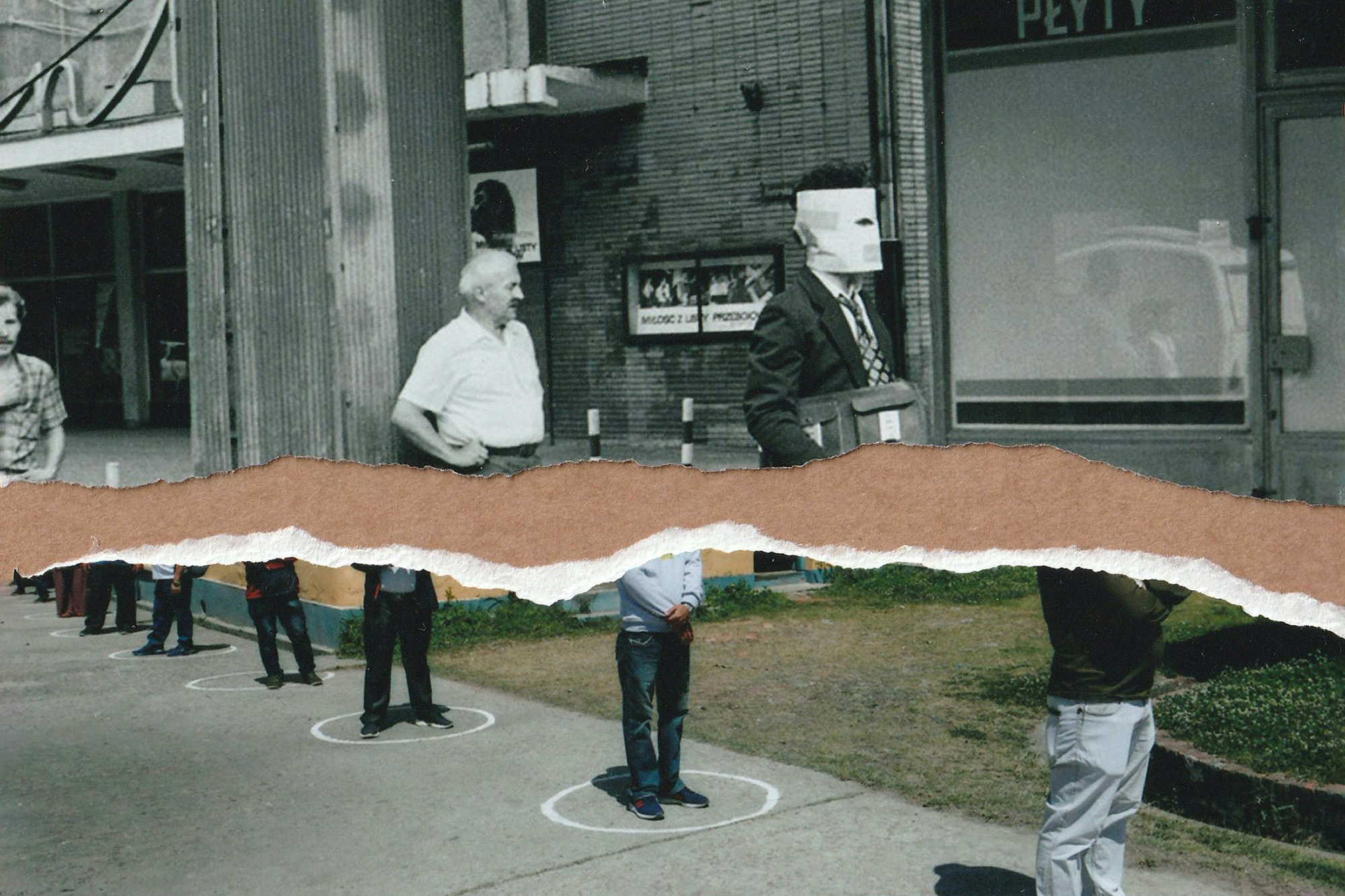

Her project Brave New World will be presented in Riga Photomonth 2021. In this series, the images from the Western lockdown realities have been juxtaposed with the archival photographs from the Eastern Bloc to create a dystopian vision of a new world with enforced social distancing rules and behavioural conditioning. The collages express the widely felt anxiety about the speed in which we have lost our civil liberties and the ease in which we have accepted to live under the draconian rules.

Where did you get the idea for your project?

After the first UK lockdown in summer last year, I saw for the first time what damage the harsh restrictions had done to our cities. The main streets in Oxford, which were usually full of crowds, were pretty much deserted. Most of the cafes and shops were still closed due to the lack of money to run them or the lack of clientele to cater for. There was a one way system for pedestrians in place which meant that if I wanted to go to the top of the street I had to stick to the left side of the pavement. It all had a very dystopian feel, which inspired me to create my own version of the ‘Brave New World’. I also saw a long queue to a bank on one of the streets. I felt that I had been there before. I was queueing with my grandma to the grocery shop. It was a long and painful process, and when we got to the counter what was left of that day’s daily supplies was only bottles of vinegar and one bar of chocolate. There was something tender in that memory – the joy of getting something, not going away empty-handed. There was also something terrifying in the striking moment of realisation that aspects of my life in the West had started evoking moments of life in a dysfunctional regime behind the Iron Curtain. The list of similarities between these two worlds turned out to be rather long: control over people’s movement, a rocketing number of reports on neighbours to the police, social interactions modelled by the state, quashed civil liberties, suspended existence, fear, etc. I wanted to explore these findings in a form of a collage by juxtaposing images of my life then with the photographs of my life now, creating a playful but also a rather grim picture. It also felt natural to distort the images somehow to highlight the damaging effect these two realities had on us. Hence, I turned to the process of tearing the photographs.

Does the socialist past still haunt you?

This was the first time ever I addressed that aspect of my Polish heritage. It was interesting to see how emotionally conflicted I am about it. I was a child in the 1980s when Poland was still part of the Eastern Bloc, so obviously there is something sentimental in recalling those memories: my time with the grandma, her garden where she kept some hens (so that she wouldn’t have to worry about egg supplies), endless hours of my roaming around with friends on a newly built socialist estate which was surrounded by fields etc. On the other hand, there was a very strict and absolutely huge socialist school to deal with, a compulsory, disgusting cup of hot milk to drink there every morning, a mean caretaker, eavesdropping, corruption, general inertia, a struggle to get hold of the basics, my parents’ anxiety about the future.

There is definitely more I’d like to explore when I look back. There is one moment in the socialist history of Poland, which is of particular interest to me. When martial law was introduced in the country at the end of 1981 and tanks appeared on the streets, my dad was working on a cargo ship, which reached a harbour in Sweden. He was offered to stay there by the Swedish government and later on to bring his family over but he hesitated. He couldn’t discuss it with my mum, there was no communication with Poland and he feared that if he stayed he could never see us again so he declined the offer. I’m quite curious to know what our alternative life could have been like if he decided to stay.

Do you think democracy is now experiencing a big challenge?

It really startled me how easily and effortlessly it was for the governments, particularly the British one, to impose pretty draconian social restrictions and lockdowns. We literarily went from being able to gather for Christmas to not being able to see anyone for weeks, from being able to travel to being forced to stay at home. It made me feel anxious about the speed in which we had lost our civil liberties and learnt to live without them. It could be the case that there is more trust in the West towards state institutions and the majority of citizens felt that this was not in place for long. However, it made me wonder what if this social experiment was here to stay. Would we have enough courage to stand up to it? And if we did, would that change anything? The reason why I’ve struck a pessimistic note is because we have seen so many protests recently – in Poland, in Hungary, in Belarus but they haven’t toppled the authoritarian governments, they haven’t changed their modes of operating and their desire to remodel the society into a patriarchal, inward looking ones.

What was the hardest thing for you during the COVID lockdowns?

I did struggle mentally with the notion of being locked down, of being confined to the area I live in, of being cut off. As time went by, I found the deepening social isolation really difficult to cope with. For example, for over two months this year we weren’t allowed to meet anyone inside or outside our house unless it was with one person for exercise. Life has become quite bare. It encompasses work, a walk, and an occasional take away coffee. Also, the physical distance between places which so magically had shrunk thanks to frequent direct flights has become real again. I haven’t been able to visit my parents who live in Poland for over a year now and I still don’t know when it will be feasible to do so. I also think that every parent who had to home-school their children and work at the same time would say that the lack of school provision was really tough. It was also equally difficult for kids, who lost all their social and physical interactions with their peers overnight.

What project are you working on at the moment?

I’m working on turning my long term project Hysterical Women inspired by writing by Sophie Gaudier-Brzeska (1872-1925) into a book form in collaboration with a brilliant book designer Victoria Forrest. I used performative aspects of hysteria to tell a visual story of Sophie’s female characters who struggled with social expectations towards women in a conservative society and failed to fulfil their creative potential. Victoria uses the same framework of hysteria or generally speaking mental illness as a female silent protest to put images and texts together. We’ve had to stop and start while working on this project as we are both parents and lockdowns really affected us but if all goes well we may have this book by autumn. Fingers crossed!